This is really not so much of a blog post as the start of trying to work out why Mexican independence got off to such a shaky start in the 1820s and 1830s, although, really, it is mostly confined to thinking about what went on there in the mid-1820s. And, to be even more specific, it is a kind of draft of some observations on what happens when your former colonial master has his (or her) hands on your vitals–I’m being polite here. I’ll dispense with footnotes and stuff for a later version that I inflict on some “scholarly” journal. This is more in the line of why didn’t most of this occur to me before? Well, the honest answer was because I really wasn’t paying attention–and because history of this sort has fallen so far out of favor with my erstwhile professional associates that there are times you say, “Why bother?” Well, the reason for bothering is my own clarification,and if this does end up in the hands of a critic, friendly or no, so much the better.

I think it’s pretty much safe to say that the old kind of imperial history–the sort of thing that my teacher Stanley Stein did–is not so much in vogue any longer. In fact, when he published what was to be (unfortunately) the last volume of what could be loosely called the merchants and monarchs project in Spain and New Spain, the time had long passed when some of Stanley’s younger colleagues could be bothered to make much sense of it. I distinctly recall one reviewer in a major journal calling the volume “old fashioned.” I won’t say Stanley was hurt by this kind of offhanded dismissal (as some of my readers know, he could take care of himself) but he did tell me he felt “deflated.” Yeah. Falling out of fashion to some callow hotshot is never fun, particularly to one who clearly has not bothered to make much of an effort to understand what a scholar is doing. We’ll leave odium scolasticum to those who have nothing better to do. God knows, there appear to be more than a few of them around.

Ok. Here we go. I have been working on and off for years now on a group of people known as “The Lizardi Gang.” I am not a particularly fast worker anyway, and this project has been interrupted by a few other ill-advised adventures for which I have mostly myself to blame.In any event, it is story that begins in the mid to late eighteenth century with commercial and political upheaval in the Spanish empire and in the rest of the Atlantic world, events that would ultimately require more than a century (at least) to work themselves out. To the extent that they were part of the process of economic globalization, not a few people may think we are still working out their implications. Fine. Not my tempo, as Terence Fletcher said in Whiplash. Haven’t seen it? Grad school set to rhythm changes.

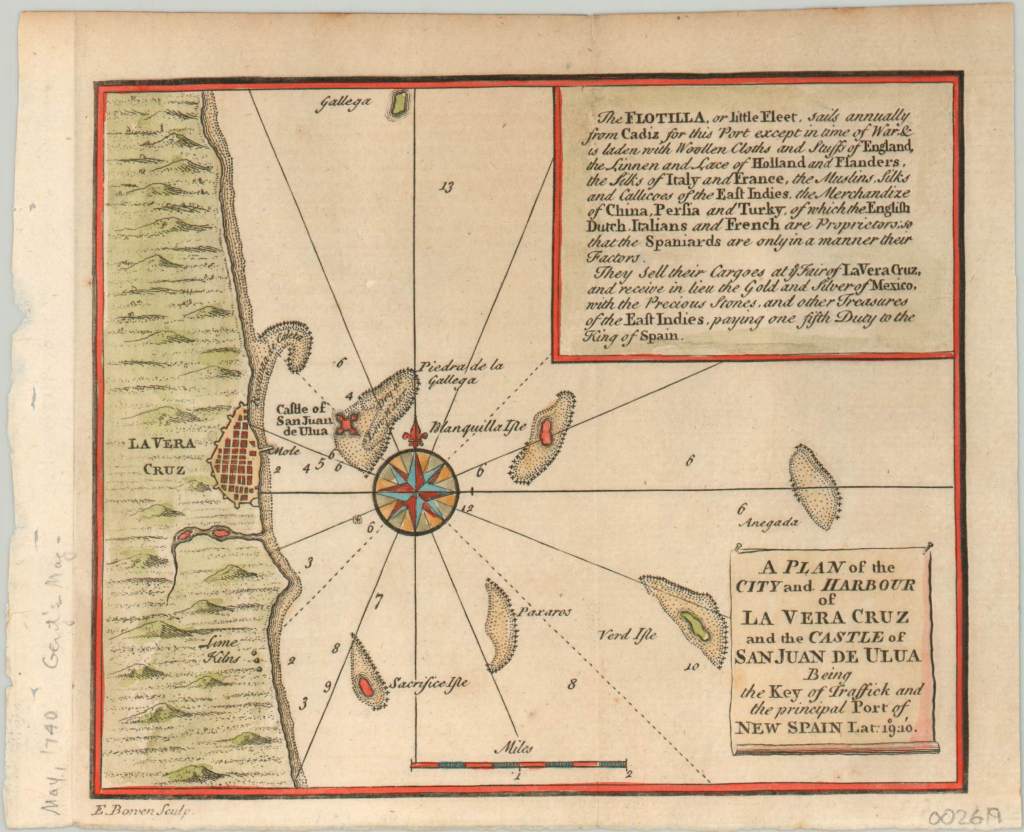

In ant event, the Lizardi Gang came to rest around the port of Veracruz on the Gulf of Mexico (yes, Virginia, the Gulf of Mexico), where they ultimately made large quantities of money through (among other activities) international trade, Spanish empire style. Because of the peculiarites of Spain’s relationship to Mexico, the tenets of mercantilism, and the economics of highly risky enterprise, a sort of select few were ultimately enabled by the powers that be to play this game. Veracruz was the single largest Atlantic port that was open to Spanish merchants trading to Mexico (not to say other flavors of merchants who wanted to trade with Mexico–French, Dutch, English, North American, what have you, whop managed to slip in) and given Mexico’s geography and topography, Veracruz became a kind of commercial chokepoint, or what the Spaniards called the garganta (the throat) of Ibero-Mexican trade. This is essential fact Number One. If you controlled the port of Veracruz, well, you had your hands on Mexico’s family jewels, because a lot, if not most, of the Atlantic trade moved through there. Now hold that thought. It was not exactly a straight shot from Veracruz into the core of New Spain, but it was the yellow brick road. And you followed it.

Around the same time that the French and the Anglo-Americans began to rethink their core ideas of popular sovereignty and political power, so too did the Spanish empire. The stupefying welter of details need not concern us–only that colonial revolution came to Mexico in 1810. And when it did, well, it was a doozy. Lots of violence, bloodshed, death and patriotic gore that lasted from 1810 into the early 1820s, and which ultimately severed the colonial bond between Spain and Mexico. But not all at once, and with lots of detours along the way. And Veracruz played a not insignificant role in the festivities.

Veracruz had long been a fortified port (San Juan de Ulua), you know with one of them hulking castle-armories-barracks-naval facilities that are so impressive to modern eyes, like El Morro in Havana, Cuba. Here. Who in their right mind would attack these behemoths? Don’t ask. Plenty tried. Mexico on the left, Cuba on the right.

In the case of San Juan de Ulua, as the peninsular Spaniards (there were Mexican Spaniards who confusingly get called creoles) yes-and-no decamped from Mexico, a garrison under the former governor of the, well, province of Veracruz (there are other names and some different administrative limits assigned to it, going back to the colonial government), a guy named Garcia Davila, decided he wasn’t going anywhere. This was because, unfortunately, the government he recognized in the peninsula (up for grabs too, to make matters worse) did not recognize the independence of Mexico, which had been negotiated by a liberal viceroy (curiously named O’Donoju….yep) whose liberal government disappeared in Spain, and to make matters worse, who then died of pleurisy even as Mexico became a de facto independent state (excuse me, Empire) under Agustin Iturbide, Emperor, some wit (maybe Simon Bolivar) called “Emperor by Grace of God and Bayonets”). Anyway, Agustin I (Emperor to You) had a pretty rough ride in his new Realm and only lasted until 1823. He suffered a fate no worse than death (you can still see his bloody shirt in a Mexican archive, cause they wasted the guy–long story: they always are), but even as The First Empire in Mexico (yes, there would be a Second forty-some years later) ended, Spanish intransigence did not. As far as the King in Spain was concerned (Ferdinand VII, 1814-1833), Mexico was still not an independent country. Yeah, yeah, the United States recognized Mexico in 1822 and Great Britain in 1825, but Spain held out until 1837. And in San Juan de Ulua, for the time being, so did Garcia Davila and the garrison, which was resupplied from Cuba, which remained faithful to Spain because it was scared to death of its own people, many of whom were African slaves bent on slitting their masters throats. Confused yet? Just wait. It gets better. And don’t worry. I can’t keep it straight without reteaching myself this episode every damn time I run over it.

So, here you got this fortified Spanish garrison sitting sort of sitting there cheek by jowl with the city of Veracruz. So far from Spain, so near to Mexico. And not going anywhere.

Oh, it was armed. I’m not exactly certainly how many cannons San Juan de Ulua had (I need to look that up) but one was quite enough. And you can imagine that relations between the Spaniards holed up in the Castle, the troops loyal to Mexico that were in Veracruz, and the merchant community were not exactly cordial. A sort of uneasy truce held for a time, but by 1823, tempers were running short. The Mexican historian Juan Ortiz Escamilla who has waded through all the details of this mess–and believe me, it was a mess–has uncovered a lot of startling detail, none of which I’ll provide here. Suffice it to say that once the Castle began to shell the city of Veracruz, matters took a turn for the worse. From our perspective, a lot of this had to do with trade through Veracruz, which had all sorts of knock on effects.

Ok. Some dubiously Geek-like stuff that has to do with the budget of whatever you want to call Mexico’s newly emerging central (not state or local) government. It was strapped for cash. This was a self-inflicted wound, but when the Mexicans kicked out the Spaniards, they sort of wanted to make sure that that no central government, theirs or otherwise, could fiscally savage them the way the Bourbon Monarchy in Spain did (another long story that had to do with Spain’s complicated relation to France after the War of Spanish Succession ended in 1713). Oversimplifying to the point of caricature, the Mexicans cut taxes so much that they reduced the fiscal capacity of the state by more than 50 percent in nominal terms. You can’t run a country on love–or pay an army, which is bad when you are still at war with your former colonial masters. So where was the money going to come from? This was a big problem all over the former Spanish colonies, but Mexico really got a dose, so by 1823, funding the central government was an issue. Yup, oversimplified, but close enough for Mexican history.

The obvious candidate inevitably, is you tax trade–especially imports. In Mexico, they also tried to tax some exports as well, such as silver, which initial was subject to a 15 percent duty, but later reduced–I believe–to 5 percent. It didn’t matter whether the silver was coined or not. You could export ingots, and this was going on in 1824. The Lizardi (and their associated kin, such as the Echeverria) were actually sending silver to Madrid to be coined. That sort of gives you an idea that this was more or less capital flight, and it was obviously a big business. If you figure that liquid purchasing power was flowing out of the country in 1824, it will give you some idea of why there was a lot of complaining about lousy markets–amusing that the same merchants complained about both, you know, who me? Also, if silver was shipped out of Mexico to be coined, it paid no mint tax in Mexico, which was another source of government revenue. So there was a fiscal dimension to this outflow as well. Finally, the presence of the Spaniards holed up in Veracruz played holy Hell with normal import traffic, much of which had to be moved to outlying islands (at the port, such as Sacrificios in the map above) That was not efficient, obviously, and Heaven only knows how much “leaked” out of the revenue stream. So customs revenues dropped which meant that the central government had less to spend. And, in Veracruz, tobacco planters had been traditionally substantial recipients of government money for what was known as the “tobacco monopoly” which required (in theory) planters to sell their harvest to the government who then used it to make tobacco products (think of the opera Carmen!). Well, that. clearly loused up demand in the region as well, so if you guess that places like Veracruz were hurting big time and off to a very bad start as independent states or provinces, you are probably right (at least I think you are). And there was still a hangover of guerilla activity from the Insurgency of 1810, and if nothing else, it raised the risk to merchandise moving and sometimes blocked it all together. If you are beginning to get the impression that Mexico was off to a possibly shaky start as an independent country, well, join the club. You want numbers? Good luck. So do I. You take what you can get. My dif-in-dif colleague seem a bit obtuse when you raise the issue. So, generally, I don’t bother any longer. The historians don’t care and the economists get annoyed. Which is why doing the economic history of Mexico the right way is the wrong career move.

And if you don’t think this stuff was costly, well, guess again. Mexico, mostly out of sheer desperation, started borrowing in the London market between 1823 and 1825. The initial nominal total was about 6.4 million pounds sterling, but astoundingly, Ortiz Escamilla, who pays attention to these things, concludes that the explicit military costs of getting the Spaniards out of San Juan de Ulua actually exceeded what the Mexicans had borrowed on London. Think about that for a moment. The Mexican foreign debt was a very big deal in the nineteenth century, and this part of it was not settled until the 1880s. So Mexico’s ability to get into the capital markets–presumably one of the benefits of independence–was seriously impaired from the get go. The actual beneficiaries of the borrowed funds are pretty hard to figure out, if you try to get beyond the broker dealers, of whom my friends the Lizardi were a part. Yeah, they made a killing. But it was blood money. Sorry to spoil the fun, but sometimes, to end well, things have got to start out well. Believe me, in Mexico in the 1820s, this was far, far from the case. While the United States was out there making “internal improvements,” Mexico was getting its clock cleaned. Sorry, but that’s scarcely an exaggeration, even if it is an oversimplification. Economists call this “falling behind.” Yeah, this what happens when the hidden hand of the market delivers a sneaky punch (I think the economist Shane Hunt said that when I was a grad student at Princeton in the Dark Ages. Smart guy). Latin American economic history for dummies. Like me.

This is really interesting. Hope you continue to flesh this out.

LikeLike

This is my retirement project. God will provide

LikeLike

You missed your calling doing standup. The line about iturbide is very funny.

LikeLike

One of the first books I read in Spanish was stein’s “La herencia colonial de America Latina.” Hooked me on Latin American history for good. The other book was halperin doghi’s “historia contemporania de America Latina, by no means an easy read in Spanish, at least then with limited Spanish skills. Both splendid books.

LikeLike

Man, that thing is no easy read in any language

LikeLike

Actually Stanley Stein’s book has held up well, at least based on its price on Amazon. $90 paperback in English.

LikeLike

Stein was scary.

LikeLike