Maybe she slipped and fell. Or maybe, in the early evening, just around sunset, she just didn’t see it coming. You know, little kids are always running around, playing, especially in groups. A group of children playing in a city street. Nothing unusual about that. Maybe tag. Maybe something else. It’s not as if it mattered. You can imagine, in your minds eye, a squealing group of little people tearing around a corner, maybe behind a parked wagon or something, yelling their heads off, not paying much attention other than to the moment. Kids are like that. In the moment. It’s not as if they have much else to think about–assuming they were a little lucky. Their awareness is is, not so much reflection. It’s why most of us remember being kids with some fondness. All we had to do was be a kid, and, especially in those days, there were no rules.

I imagine this little group of wild people was shouting in some amusing mixture of English and Italian. Some of them had been born over there. Some here. They probably all spoke Italian, somehow mutually intelligible, especially if their parents came from the South. Dialect you know, and barely comprehensible to us now. “Vieni qui!” Get over here! That much we would have understood. It is the categorical imperative of childhood. Works in church, school, at home, or playing. Anywhere a few were gathered. Laughter and love. And energy. Lots of it. Like small car, big engines.

Anyway, one of those kids was named Concetta Delia. She was eight years old (or maybe six, or maybe five), or so the newspaper said. And she would forever be. She, Concetta, was of another time. The Great War had not yet begun, so she was still part of the nineteenth century. Literally. Italy was still ruled by a King, Victor Emmanuel III. Italy, the nation-state, was barely half a century old. If Concetta knew anything about this stuff, she was in one of those odd moments when Kings and Presidents (and the occasional Emperor) decided the fate of some abstract nation, while little kids, as usual, played in the streets. But, now, increasingly city streets, which too were also an artifact of two centuries: a country lane meeting paving for the first time. A place for horses and manure now yielding quickly to automobiles, “power wagons” and grease stains. It happened slowly and then all at once. The race into the contemporary world had begun. And it claimed its casualties, as any race would. Concetta Delia was one of them.

Concetta’s parents were Pietro and Maddalena, then in their early thirties. I have no photos of them. I wish I did. They were my maternal great grandparents. I was fortunate to know them as an elderly couple when my Grandmother, Francis Villari, would take me to visit them at 809 Cross Street, “down the house,” as we always said, in South Philly.They were always very sweet to me–I was about 5 or 6 years old. Little did I know that Francis, my Grandmom, had a little sister, Concetta because, very confusingly, there was in the 1950s another Concetta, the only one I ever knew. She too was my Grandmom’s younger sister. There were two Concettas: one survived childhood. The other did not. Until this year, I had absolutely no idea. It’s funny. Italian families are inveterate talkers–communicative as songbirds–but they hide their secrets well. I learned that lesson as a kid. When to talk, and when to shut up. I don’t think I ever learned it well enough, but I got the idea. Some stuff you didn’t talk about. Concetta was obviously one of the things you never talked about. Never tell anyone outside the family, that sort of thing…….

It’s funny, you know. Because my Grandmother, Frances Villari, did sometimes let drop details about her childhood. I remember her telling me she had had scarlet fever. And I’m pretty sure she mentioned typhoid too. In Philly, that would have been during an outbreak in 1911 when the city’s water got polluted by a broken main in a pumping station and the city drew on the Schuylkill River, in which, upstream, God only knew what you toxic waste you got. Not for nothing did we call Philly Water “Schuylkill Punch” when I was a kid. . Anyway, Grandmom told me about this stuff, but of a dead little sister. Nothing. Maybe because I was just a little kid myself, and she didn’t want to frighten me. Hell, I was then no older than Concetta had been.

Article from May 9, 1914 Harrisburg Daily Independent (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania) <!— –>https://www.newspapers.com/nextstatic/embed.js

And if that wouldn’t frighten the Hell out of a little kid, what would. Especially one who had a trolley line running in front his West Philly home. Trolleys, albeit horse drawn, had been in that area since the 1870. In South Philly,electrified street cars had come in by the late 1890s. My guess is that they still probably looked something like this, maybe a little smaller.

You have to have some sense of what kind of neighborhood this part of South Philly was. It was sort of at the southern fringe of civilization. That doesn’t mean it was bad, but it was not exactly Parkside either. If you went about 3 miles South of 8th and Kimball, you would have hit an undeveloped part of the city known as The Neck. It was marshy, kind of ramshackle and home to Philadelphia’s resident colony of pig farmers, who made a living supplying the city’s 9th Street market with pork producer, including offal. It was not exactly a source of civic pride, even in 1914. It had the reputation as a place you went and got your ass kicked. So I’d guess Concetta lived in a place which was the bottom of the ladder of upward mobility for Italian immigrants, which her sister Frances certainly saw in her lifetime. Suburban Penfield, where Frances died at 94, was another world from pig farmers and The Neck. So these guys were one step up from The Neck. They were lucky to be there. Remember, they left Italy behind.

The Neck, a somewhat optimistic view

10th and Kimball, looking East. No, it isn’t a Hopper painting, but you see where he got the inspiration

Since the accident virtually happened on their doorstep, they would have known immediately. Probably a banging on the door, followed by screaming and shouting, in Italian, the neighbors. I can imagine Maddalena and Pietro running out into the street. And oh Lord, what did they see, Their child, Concetta, beneath the wheels of a trolley. It is almost obscene to try to imagine with a gathering crowd, people shouting, the driver frantic, my Great Grandmother and Grandfather in some frozen state of hysteria and shock. What do you do? I’m sure the trolley driver was petrified and would not move the car, because, as the story says, they called for a jack to raise the car off Concetta. God only knows how long it took for the jack to get there, to raise the car, and to extract the child’s lifeless, broken body. She was taken to Pennsylvania Hospital, at 8th and Spruce. That’s less than a mile, but it must have seemed like another planet. My guess is by motorized ambulance, but, really who knows? It could have been horse and wagon. My Lord, they may have physically carried her there, frantic. Only God knows now. I imagine the scene in different ways, each progressively more ghastly. Concetta was pronounced dead at Pennsylvania Hospital.

And now, I know almost nothing more. What I do know, from looking at the parish death register, is that little children died this way. Another three year old in February (1915?) “morto sotto un carro di transporto all’Ospedale Pennsylvania.” (dead under a transport cart, Pennsylvania Hospital) You can imagine the WASP doctors’ heads shaking. Why don’t they watch their children more carefully? Italians. What can you expect? You can fill in the mental blanks. They never change, do they? What can you expect from immigrants?

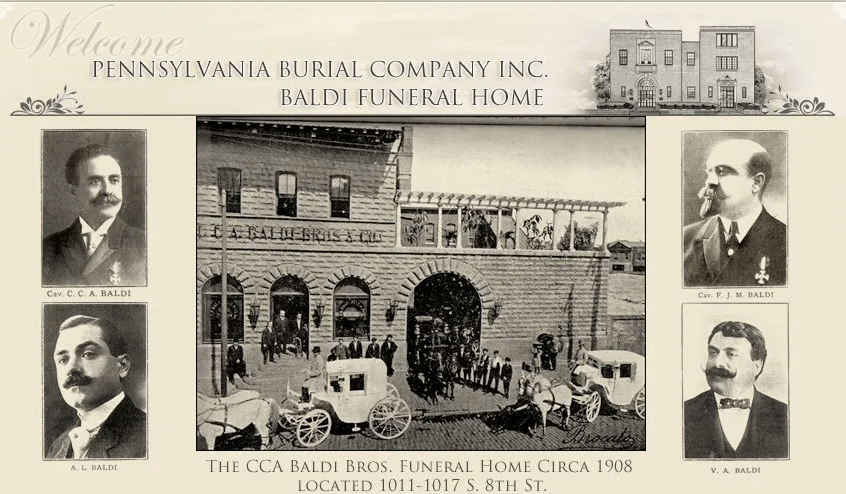

So a million questions run through my mind? Did anyone sleep for days after? Was there any kind of wake (did that even figure in death rituals in Italy then)? When was the funeral mass? There must have been one, no? How on Earth did they pay for it? How did they get the little girl to Holy Cross Cemetery in Yeadon? As the crow flies, it must be 6 or 7 miles, but you’d have to get across the Schuylkill River–in 1914, how or where where? There were ferries, true enough, and at least one bridge, but that was to West Philadelphia. Was there a procession, which even then was a tradition among Italians in America? Who bought the grave? Was there some kind of mutual aid among Immigrants there? You can see what Baldi Funeral Home looked like in 1908. I can’t imagine the child got that treatment, you know? High-end Edwardian. Probably a little more like the photo at the very bottom. How did they get out to Yeadon to visit the grave, because they must have. You know, Italians are not allergic to graves. How long did they mourn? She died on May 8 and was buried on May 11, which seems remarkably hurried. Or maybe it wasn’t.

My God, I know nothing about my own people. I don’t even know if I am asking sensible questions. I do know I have been thinking about this almost since I first ran across it. The story haunts me. My ignorance haunts me. The world as it was before I was haunts me. Draw your own conclusions. Who am I?

And speaking of haunting, the Delia ultimately moved to 913 Cross Street (https://thisgameisovercom.wordpress.com/wp-admin/post.php?post=1090&action=edit), again, nearby, less than a mile walking today. It was a bigger house and the family was growing. Another daughter, born in 1917, was again named Concetta, whom I knew as my Aunt Connie. And I am told by a church archivist in Philadelphia, Elissa Torre-Lewis, who has been of great help to me, that the practice of preserving the name this way was not uncommon. Another cousin, a Delia, told me she heard stories that Concetta lived upstairs on Cross Street, and occasionally came down to the first floor to make her ghostly presence known.

I never did see the second floor of that house in all the time I went down to South Philly to visit. Not once. Now I know why. But the next time I get out to Holy Cross, I’m going to find Concetta and leave a flower. Because I now know where she resides. In aeternum, amen.

–>

–>