Pa todos mis amigos de Mexico, sin rencor y sin politica, pero sí con mucho amor.

Let me make it clear from the outset. I do not regard this as any more than a glorified opinion piece. It is not an academic study. No one has reviewed it. And I, as much as anyone, am aware that my conclusions my be quite mistaken. Still, when someone asks me a question of interest, I can rarely resist trying to answer it. Like Sly Stone said, sometimes I’m right, sometimes I’m wrong, my own beliefs are in this song. And these are my own beliefs, buttressed by some very elementary international financial accounting, whatever statistics I could find, and curiosity. Please do not construe these as findings. Because that would be to give them an status they do not possess. OK? We clear? You quote me (or anyone I cite) at your own risk.

I’m going to state my conclusions first, so that no one is wondering what is going on. And I am going to simplify matters, as much for myself as for you. Recently, there has been a great deal of speculation that Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO), the President of Mexico, has been actually reducing poverty there. And if that is so, it is a very, very big deal.

It is a very big deal because Mexico is a middle income country, but given profound inequalities in the distribution of income and wealth (a bit like Texas), average figures, like per capita income, may be somewhat deceptive. For the most part, the standard view of Mexico is that about half of the population, arbitrarily measured, is poor. When I first went there in the 1970s, that was the estimate you always got–closely related to another figure, that 40 percent of the population subsisted on beans and tortilla. If you were living, as many of us were, in urban areas (like Mexico City) and were ensconced among middle class people (we lived in Roma Sur, in the DF, as in the movie, Roma, if you’ve seen it) and our friends were mostly middle class. Not affluent, but not really hurting either. If you went looking, especially in the countryside, the deprivation of many people, essentially landless peasants in a society in which land was still an important marker of wealth, then you could start to see the poverty. And see it some of us did, in trips to Jalisco or Michoacán or Guerrero or Puebla. Seeing was and was not–to some extent–believing, because what you believed depended on what you saw. And what you saw was what you wanted to see.

It is also a very big deal because, to put in plainly, since 1980, the Mexican economy has not done very well. Especially when you consider that in 1970, Mexico was hailed as a model for the rest of the developing world, and the beneficiary of some sort of “Mexican miracle.” Since I am writing a book about all of this (which, God willing, will see the light of day soon), I’m not going to drown you in details other than one. According to Tim Kehoe, an economist at Minnesota, between 1950 and 1980, real GDP there grew by 6.5 percent per year. Between 1981 and 1995, the figure fell to 1.3 percent per year. Yup. You got that right. Starting in 1995, real GDP grew by 3.7 percent per year. Overall, if you want to conclude Mexico fell off a cliff, go conclude. Why, believe me, is a complicated matter. Brutally complicated, That it happened, no doubt. Ask any who is really familiar with the case–and please, not someone who just spent a week in Cancún or took a trip to Monterrey and came back impressed.

The reason this matters is that the best cure for poverty is economic growth. If you want fewer poor people, create opportunity for them to work, consume, save, and invest. In other words, grow. You cannot get rid of poverty without economic growth, although it is entirely possible to limit the part of the population that benefits from growth–another essential part of the Mexican story. Again, the causes are brutally complicated. Complicated is no fun. Brutal oversimplification is much, much easier. Much easier to proclaim “They are poor because we are rich.” Believe me, under various labels, this is about as far as it gets among many right-minded historians, sociologists, and political scientists. An even simpler way of putting is “Capitalism did it all.” Sure, whatever. This is not a discussion that anybody resolves in some blog post. If ever.

So, before this really gets rolling and very messy, I want to state my conclusion: AMLO has reduced the number of people living in poverty in Mexico. Whether, given the means taken, he or a subsequent government of the stripe of MORENA (his “party”) can continue to do so is unclear. My gut says “no,” but then again, there is a question of short versus long term. Mexico has in the past shown itself willing to do the wrong thing for the right reason if some future government has to pick up the pieces of a resulting catastrophe. If this strikes you as cynical, look at the United States. We are no different, really. It is a question of political costs and benefits. We reap the benefits now. The future is someone else’s problem. We have “high rates of discount.” Give it to me now and the Hell with the future. Still, reducing poverty in Mexico is no small feat. The question is whether the means of doing so can produce permanent results. I think the answer is no.

Let me give you a really stupid explanation. Suppose you are wearing trousers with two pockets. In one you have $20. In the other you have $80. A poor pocket and a rich one, ok?If you decide to move $10 from the rich pocket to the poor one, you are, on the whole, no better off. You have $100, just as before. But, for now, the poor pocket is better off, because it has $30. The rich is a little worse off at $70. Now how long can you do this? Well, obviously, the limit is $50/$50. It’s not as if you’re creating any new wealth. You’re just transferring existing wealth from one pocket to the other. In theory, at least, you can make the poor pocket rich and the rich pocket poor. What have you accomplished? On balance, nothing. Maybe you make the left hand feel wealthier for a while, but only at the expense of the right. That is what a transfer is all about. The only way you are really better off is by going out and earning more. Then you can decide which pocket gets it. And don’t kid yourself. There are plenty of ways of seeing that one pocket or the other ends up with a larger share, mostly through tax laws that it takes a CPA or PhD to fathom. No, it isn’t just the “magic if the market.” If that were true, the United States since the late 1970s would look considerably different. And better.

Now, you my say, Lord, that is a terrible oversimplification. And it is, no doubt. But you get the message. If you move wealth around without creating anything new, so what? Some people feel better off. Some feel worse off. The net result is zero.

From what I can tell, what Andrés Manuel is doing in Mexico is more or less this. He’s is moving money from one pocket to the other. He is not really creating much if any new wealth. So this can only go on so long. It is, as we like to say in English, smoke and mirrors. Smoke and mirrors can work for a while, but not forever.

For the moment, let’s forget the politics of all this, although you can clearly see the “residents” of one pocket will be ecstatic. The residents of the other, Not so much. Is there any convincing evidence that this is what is going on. Well, honestly, yes and no. Enough to make me suspicious, but not enough to convince me. So if you said, well is Andrés Manuel (which is what Mexicans fondly call him) making Mexico better off, I’d be agnostic. Is he making some people better off. Sure. And they adore him. Is he making others worse off. Sure. And they detest him. Here, have a look-see. These are AMLO’s ratings since 2018……(approval is green)

Right now, AMLO’s approval ratings are 70 percent. They may have been higher 4 years ago, but Joe Biden would love to have a 70 percent approval rating. Practically speaking, this probably means that AMLO will have a big voice in who succeeds him. That would be Claudia Sheinbaum, 61, also of MORENA. Don’t bet against her. The opposition, such as it is, is composed of what Mexicans tend to call the PRIAN, an amalgam of the old PRI governing party, and the opposition PAN party from which presidents Vicente Fox (2000-2006) and Felipe Calderón (2006-2012) were drawn. Neither has much of a following these days. Obviously. Calderón is one of the most detested figures in Mexico for setting the military against the narco-cartels (and maybe melding them too). The Council on Foreign Relations estimates 300,000 people in Mexico have died from drug-related violence since 2006. The narcos’ record-keeping is, understandably, a little spotty.

But let us get back to the matter at hand. Why think that AMLO is playing some kind of shell game in Mexico and winning big? Well, in the United States, the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) and The Atlantic Monthly (David Frum, Anne Applebaum) ran very hostile pieces on the threat that Andrés Manuel represents to democracy in Mexico, although aside from Shannon O’Neal of the CFR, I don’t think much of the credentials of the people running him down in the Atlantic. They are very smart, but don’t know beans–forgive the pun–about Mexico. And they are coming at things from the side of political institutions. They may well have a point about AMLO’s authoritarian tastes, but that is not what interests us.

We are going to have to go at things indirectly. There have been critical analysis of AMLO’s economics, but I’d prefer to draw my own conclusions, however flawed they may be. You can go out and read other takes on this, and probably should.

First: it takes economic growth to eliminate poverty. There has to be more stuff–goods and services available–and people with the means to purchase them. For years now, economists have been getting away only-GPP/head measures in favor of a much broader “capabilities” definition, and in Mexico, CONEVAl (Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Politica Social) has been a pioneer in using such indicators as education, health and basic services to frame the dollar estimates. Because I am one person, and not CONEVAL, I am going to stick to the traditional “poverty line” estimates knowing full well that the broader measure is better. By all means, go to the CONEVAL (https://www.coneval.org.mx )site and judge for yourself. Summarizing the report in the Washington Post, with poverty defined as $244 a month in urban areas and about $175 in rural areas, in 2023, CONEVAL said that 56 million Mexicans lived under the poverty line. That’s about 44 percent of the population, which is well down from the customarily quoted 50 percent. About 33 percent of the population were too poor to buy the basic food basket, so celebration may strike you as premature. Celebrate, nevertheless, AMLO did: “I can die at peace.”

To be sure, I do not doubt CONEVAL’s figures. I do not think anyone has cooked the books. My principal question is whether the reduction in poverty was achieved by sustainable means. And by that I mean by higher, sustained growth–not just moving money from one pocket to another, which is how we will crudely define transfer payments. Now your inclination may be to say–and I half agree–who cares? The money spends all the same and reducing poverty in a poor country is clear Priority One. So what’s to complain about?

Well, I have already hinted that transfers have their limits, because in themselves, they create no new wealth (and yes, you can think of ways that transfers could, in principle, create new wealth by raising investment in physical or human capital). Whether that is what is happening in Mexico is unclear, but my gut hunch and some of the data say no. We can come back to this point in a bit. If you have followed debates over Social Security in the United States, you’ll already have some feel for the discussion. You got to have enough actively productive people to support the ones who are less productive (not necessarily unproductive), or the burden of the scheme on the working (or saving) population becomes intolerable. You can’t get blood from a stone, especially when there are no stones. So, why doubt that AMLO’s project is any less than a roaring success?

Well, for one thing, growth in Mexico is nothing to write home about, and has not been since the Miracle days prior to 1982. According to the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development)–and I cannot but think this is probably the best I am going to get–per capita disposable income in 2021 was about 12 percent higher than it was in 2018 (technically, parity prices). That’s about 4 percent per year, even if we figure COVID kicked in in 2020 and really depressed things (it did, of course). How does growth which was clearly inferior to what was registered during the years of the “Mexican Miracle” reduce poverty when poverty stood at 50 percent of the population and growth rates were much higher? Again, I’m not saying that AMLO has not reduced poverty or people in poverty in Mexico. What I am saying is that it is dubious, to put it mildly, that this is coming through economic growth when growth is really no better now than it was 20 years ago, and Vicente Fox was promising to raise it to 7 percent a year–which did not happen.

Of course, you could say, well, AMLO said he was going to govern in the name of the poor and that is exactly what he has done. Which is precisely why his approval is sky high. There are fewer people living in poverty in Mexico now than before, whatever the growth rate says. Period. Ok, but I am going back to my original question. If poverty reduction is not coming from growth–and it probably isn’t–then there aren’t many realistic alternatives.

Well, what about all the Mexicans now living in the United States? Don’t they always talk about immigrant remittances? Well, absolutely, and according to Jazmin Rangel of the Wilson Center (a very reputable shop) https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/infographic-remittances-mexico-reach-historic-high in Washington, DC, 2021 was a record year for Mexican remittances (and the trend has continued) from the United States, which account for about 4 percent of Mexican GDP, and flowing mostly to Michoacan, Jalisco and Guerrero, states where poverty is endemic. Technically, I do not think remittances would show up in Mexican GDP (GNP may be another story, but I won’t swear to it), so you really cannot say the AMLO is getting manna from Heaven, even if he is. No doubt an injection that size into the Mexican economy has knock on (“multiplier”) effects of some magnitude, but in the absence of any attempt at measurement, I’d have to say your guess is as good as mine what it might be.

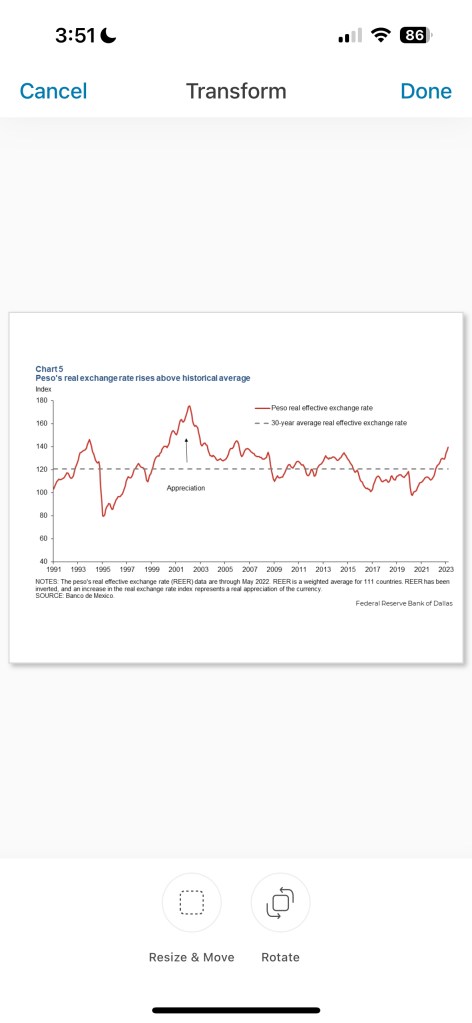

Of potentially greater importance is a boom in foreign direct investment in Mexico, particularly in 2022 and 2023. The source of much of this is sometimes called “nearshoring,” which essentially means moving investment from places like China to Mexico for a variety of reasons that range from political factors to supply chain management. Mexico’s figure for direct investment has risen at least 30 percent in 2023 to over 33 billion dollars. While that bodes well for the future, no doubt, it really has no short term effect on poverty other than perhaps indirectly through the exchange rate. Between foreign remittances and direct investment, the Mexican peso has risen over 20 percent against the dollar over the past two years, which is substantial. In fact, if we look at the real effective exchange rate again the dollar, the peso is above its 30 year average. And if you consider a parity rate, the peso is closer to 40 percent above it if figures from the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank are to be believed. This is another thing I want to come back to, because it is a double-edged sword. Forgive my clumsy transfer, but I am no WordPress maven. I assume 100 is parity (that is, a unit of currency can buy the same good in either country). So 140 means the peso can buy 40 percent more in dollar terms. Back in the day, we would think that wildly “overvalued”, but, oh brave New World.

Remember we said back in the beginning that there was a, well, right way and a wrong way to eliminate poverty? That the right way was growth, and the, well, smoke and mirrors way was moving purchasing power from one pocket to another. Well, since we pretty much eliminated growth as the way AMLO was working this new miracle, we’re sort of stuck. We said direct investment is promising, but rarely a quick fix (although a very good thing!). Remittances from Mexicans living in the US might be helping AMLO out, but it would be hard to say exactly how much, other than it’s probably not trivial. The peso has been driven way up above its “parity” by these two things (at least, because dollars gt exchanged for pesos). That may , or may not be a good thing. Politicians usually love strong currencies because they equate them with, well, you know–size matters. And a lot of Mexicans, from what I can read in the social media, have the same idea. It’s wrong-headed, but who cares, for now?

Well, what about the magic pocket movements? That is, in effect, a sort of economic shell game, but then look how many people want to play–and there is no more Mexican game other than dominoes. Guess what? You want my best guess as to what AMLO is doing? I’ll translate the Spanish for you. This is from a presentation called “Poverty in Mexico” by by a gentleman named John Scott, who is affiliated with CONEVAL, among other things. I don’t know him, but I wish I did, because he is no one’s fool.

The chart in Spanish is a breakdown of the source and effect of transfer payments in Mexico under AMLO. Look at the left panel, ok? These colored bars are transfers as a share of GDP, and the colors show the categories under which the transfers occur. First, since the beginning of AMLO’s six year presidency or sexenio in 2018, the share of GDP going to transfers has doubled. Now, you might say, big deal, to 1.4 percent. Immigrants remittances are more than twice that as a share of GDP, so why not say this is Mexicans helping Mexicans out of poverty, not AMLO transferring Mexico out of poverty? Well, for one thing, AMLO can’t take any credit for the fact that so many of his people have left that they are effectively bigger than his antipoverty program. But, well, you could say that if you were so inclined, no? Why not? Now the nature and the distribution of the transfers has changed significantly too, and that has been very controversial and not to everyone’s liking (one of the reasons the bars change colors). But we’ll leave that aside, even if it isn’t inconsequential. It just makes an already complicated picture even more complicated.

Now in a graph that I don’t reproduce, Scott shows that the proportion of the population in poverty during AMLO’s sexenio has indeed fallen, and that in the most recent years, maybe 7 percent of the entire reduction in poverty (“Marginal impact of transfers”) comes from transfers. Well, what about the rest? The honest answer is I do not know, because there is no obvious source (growth, or more technically, productivity change) to explain the reduction.Because we know how big growth has –or has not been–in Mexico. Even if, at the margin, immigrant remittances were more important, we would be far from accounting for the entire reduction of people in poverty. It has to come from somewhere. So until someone, so to speak, places his or her hand in the wounds, I remain at best agnostic as to causes. Again, I don’t think there is much doubt that AMLO has done what he says he has done. But transfers account, at most, for a part of what we can see, so the entire subject remains a bit mysterious. I have no doubts about the professionalism of CONEVAL. Mexico is not Argentina, Turkey, or worse.

So now what? Where do we go from here? Well, for one thing, it is clear that AMLO, his vaunted allegiance to something he called “republican austerity” notwithstanding, has loosened the purse strings. The fiscal deficit of the central government (with the exception of a blow up in COVID years) has run about 5 percent of GDP under AMLO (that is, the excess of government spending over revenue), which is actually somewhat looser than his recent predecessors. So government spending relative to revenue (relative to overall production) has actually gone up. It is conceivable that this is why poverty has fallen under AMLO–not just transfer payments, but good old fashioned Keynesian deficit spending. I don’t have any good simulation software for Mexico at hand–and no, if I were so inclined to do that, I would publishing the results in a more, well, formal outlet. But it is not outside the realm of possibility, as far as I know. If you disagree, please, by all means, let me know. Although, again, I am not sure why this would not show up in the growth figures that Mexico and the OECD provide. I do know that other analysts have made somewhat alarming pronouncements about Mexico losing control of its hard-won fiscal stability, The highly reputable Wilson Center being one of them. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/mexicos-2024-public-debt-surge-defying-prudence-cause-concern I’m really not sure this is called for, but, face it, when Mexico lost control in the 1970s, the beginnings of the deterioration in the late 1960s were imperceptible at the time. Even after the colossal disaster of the student massacre at Tlatelolco in 1968, nobody saw what was coming. If you don’t believe me, go back and look at the Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS) for Mexico after 1968–the diplomatic chatter we generated.The overall verdict was sanguine, the heavy handedness and brutality of the government of Gustavo Diaz Ordaz notwithstanding.

We also know that Mexico’s current account is in deficit. What this means, plainly, is that Mexico must be borrowing (either public or private), because the country is consuming more than it is producing. This is foreign borrowing, because that is the only way you can get someone else to give you their stuff to consume if you are not making enough yourself. In a way, given how high the Mexico peso is (since the currency floats, I won’t say “overvalued”, because open markets don’t overvalue, right?), the deficit is hardly a surprise, but having both a fiscal and a current account deficit is, well, not good economic juju, particularly for a country like Mexico whose fiscal implosion in the 1970s and 1980s is hardly ancient history. No one–and I mean no one–wants to go back to the good old days.

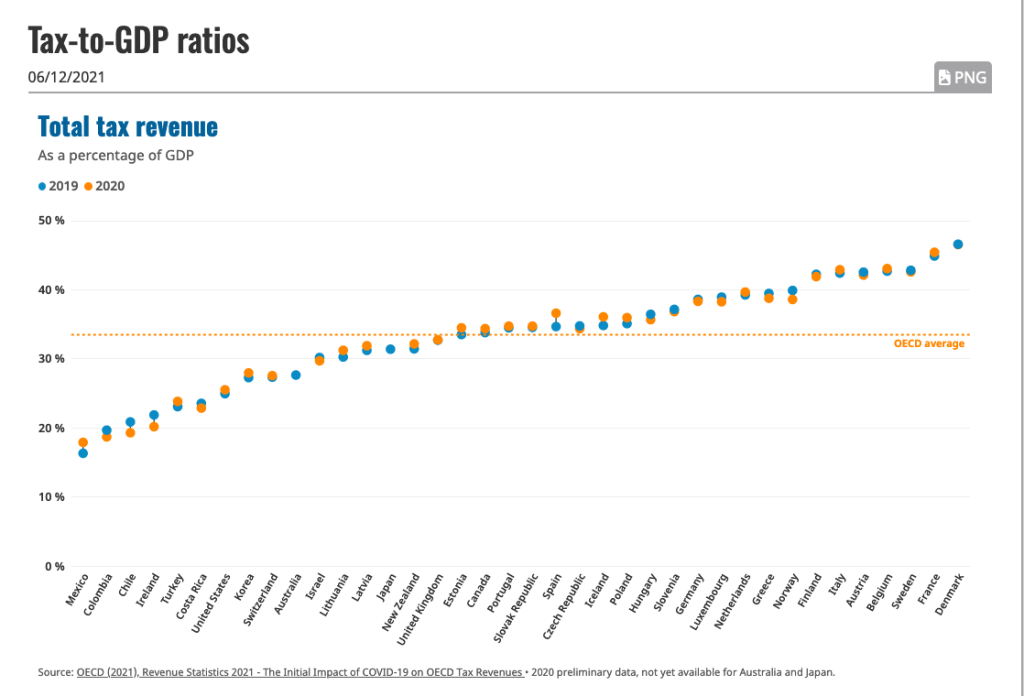

So, what is the answer. Do you simply say you have to tolerate social injustice because that is good economics? I have friends who say stuff like that and I roll my old eyes when they do. Mexico still ranks dead last in the OECD in the share of GDP taken as taxes (see below) so what does that tell you? If Mexico were only average by OECD standards, it would collect a great deal more tax revenue (one of these days I’ll back-of-the-envelope how much), and then

imagine what the government could do. Without borrowing. But many know that tax reform in Mexico has been a touchy subject since the British economist Nicholas Kaldor went there in 1960 and wrote a report on reform that was never (to my knowledge) published and was written in hugger-mugger somewhere outside Mexico City. In any event, while MORENA may build airports, trains and other pharonic monuments to AMLO’s restless ambitions, I haven’t heard anything about tax reform.

Whatever Andres Manuel is, he’s no fool. No one wants to be in the rich pocket when there are still an awful lot left in the poor one. And AMLO, populist or not, leftist or not, knows that.

Wow, quite a treatise to sort of disavow in the first paragraph. This is really good and I learned something. When it comes to Mexico, most Americans don’t know anything. I am one of those Americans. This is some substantial “spare time” work and I enjoyed reading it. The rich/poor pocket metaphor is a perfect descriptor to aid in understanding. So bottom line? Mexico needs growth because transfers have run their course? That will be the game going forward for AMLO.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dude, you make me happy because that’s just about what I intended to say. Sometimes I write this stuff to make myself understand what is going on. This was just the case here

LikeLike

Thanks for all the time you devoted to research and explain this, Richard. We’re likely to see a second term of Morena in power because, as you rightly said, people on the trousers’ left pocket felt that one way or another money was coming to their side so, thankful as Mexicans are, they’ll vote for whoever AMLO tells them to. However, I couldn’t help but remember something I saw when we went on a five-day vacation in november 2022 to the small town of Bacalar in Quintana Roo, near the frontier with Belize. Amid all the poverty (because tourist dollars and job posts only flow to Cancún and the Riviera Maya), Bacalar is a paradise, the only place in the Yucatán peninsula where you can find a significant body of surface waters because thousands of years ago some cenotes overflowed and formed a group of connected lakes fed by underground currents, and whose difference of depths generates an amazing visual effect under sunlight (that’s why it’s called the Laguna de Siete Colores).

It’s but inevitable that these wonder came to the attention of the planners of the Tren Maya, and so the train’s route will pass nearby. A local taxi driver in Bacalar explained to us that, since there was not a previous federal railroad line that could be used, it was necessary for the Government to buy plots of land from a large group of Mayan peasants in the area in order to draw it; our driver’s father was one of them. He put it plainly: his father received more money than he’s ever won during all of his lifetime ploughing all of his land. So it was no surprise that from Chetumal to Bacalar all fences on the side of the road were painted with welcoming signs for Claudia Sheinbaum’s soon-expected visit to Quintana Roo. The thing is: this was a once-in-a-lifetime offer. You can’t build another Tren Maya in the Yucatán peninsula now that it’s been finished. People have been promised that this will bring economic growth, and the cash they got for giving their land away was received as an advance of the upcoming prosperity. How lasting will the left-pocket effect be for AMLO’s successor if (as I’m afraid) the economy created by the Tren Maya results in a social nightmare as present-day Acapulco, or, in the best case, in another paradise of inequality and discrimination as the neighboring Riviera Maya?

LikeLike

You see. You know what’s happening because you are there. and that is worth far more than some guy in Texas staring at numbers could say. AMLO doesn’t pass the sniff test. Something smells wrong but what do I know? What concerns me is that I have seen this movie already—i was there for the first showing and didn’t really understand what I was seeing. But I saw my friends get royally screwed by prople likr Echrverria snd Lopez Portillo. i heard the stories from Mexican economists working here, especially guys like Abel Beltran del Rio at Penn, honorable people, serious, and disgusted. i am under no illusions. The EU is about as corrupt, but hides it better and has a better narrative

I miss my friends a lot. Guys like you. How this will all end, only God knows. Un abrazo, compañero

LikeLike

I should add I am rereading Aguilar Camin’s Despues del Milagro. I hd to laugh: p. 285 “la urgencia mexicana de los anos noventa solo puede resumirse en una palabra: crecimiento.” Needless to say, I wonder why this book never got the press in the LASA/CLAH circles that it should have.

LikeLike

Way off subject, but very glad you’re still alive and kicking, as well as educating~and continuing with your humor. Had you in grad school at Texas in the late 80s and you were outstanding I hope to write something of substance next time around.

LikeLike

Wow. How are you!!!!

LikeLike

doing well. Had you for historical methods and the economic history of Latin America. Both superb.

great blog. Can’t stop reading it-my wife is about to take away my phone. Man, you are still funny and a great historian. Arno Mayer meets Abe Vigoda or Rodney Dangerfield.

read the piece that touched on the ejidos and agricultural productivity (or the lack there of) and its drag on the economy. Have a bit of first hand knowledge and would like to comment briefly when I have time.

Thank you for a blog that makes history (and by that I mean intelligent history) accessible to the layperson.

LikeLike

I’m honored. Really. Coming from you

LikeLike

Thank you You made my year

LikeLike

made my year

LikeLike

Dr. Salvucci:

When money goes from one pocket to the other, how much disappears in the form of government skimming, for lack of a better term. I love Mexico but as everyone knows corruption is endemic and it starts with the government. In other words, how much GDP growth is lost due to folks taking their cut while money changes pockets?

years ago I had the opportunity to do insurance work in Juarez, and lord, everybody had their hands out. Everything revolved around the mordida(the bite) also referred to in Juarez as “what is good for me is good for you,” and “show loyalty.” Colorful Juarez terms. But all of the biting adds up to big costs. To be fair, the juarenos have nothing on the nice folks from Philadelphia, formerly known as the insurance fraud capital of the US. But that is another story.

Anyway I’ll shut up and see if dr Salvucci can give guidance on the economic cost of corruption.

LikeLike

I can, but you’ll have to wait a bit and see what the congnoscenti say……

LikeLike