Fly, Eagles, Fly!

Ok. Now that I got my daily dose of filiopatriotism out of the way, we can return to more serious stuff. My faithful readers (hello?) know that I am sort of hung up on the history of Haddington (West Philly) and Penn Wynne (Montgomery Country, just outside the city limits). I grew up there and, to a lesser degree, in South Philly, so even after 45 years’ absence–that’s just hard to believe–the pull is still strong. Every time I run into something new, an artifact that gets me to see something a bit differently, I sort of go crazy. So here we are again.

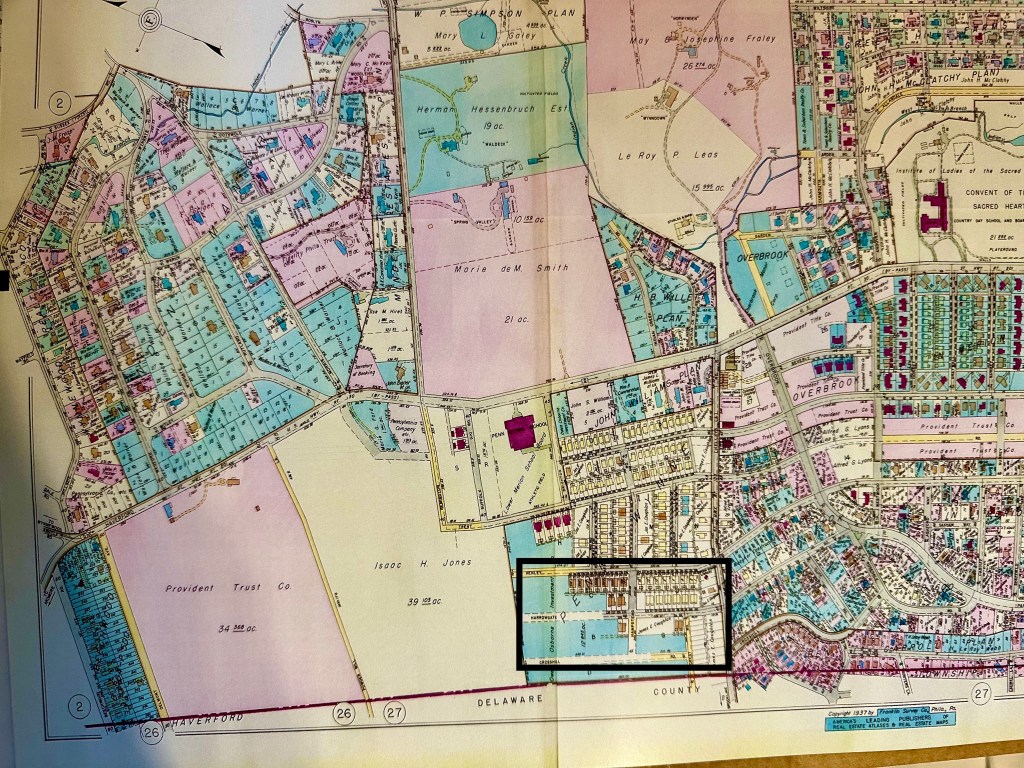

I recently found a 1937 atlas-map of Penn Wynne, very detailed, and, I think, not entirely accurate, but it made me realize that I hadn’t really understood how that particular streetcar suburb came to be. In all honestly, to do this right, I should be there, where I can look at deed books in Norristown and go bugging local institutions for stuff they have in their basements and attics (like Lower Merion township, but that isn’t going to happen today). Maybe someday someone will write a proper book using the new materials and techniques (like GIS) with which we are now blessed. But for now, another incremental contribution.

I of course knew that Penn Wynne-Overbrook Hills was carved out of what had once been farmland and substantial estates. All of Philadelphia, more or less, had developed that way. And even in my youth, I could see the process at work in Northeast Philadelphia, Elkins Park, Springfield, Broomall, and any number of other of postwar developments. My family visited many of them in the 1950s when we were just starting to move away from our extended family in West Philadelphia, and I remember tramping through model homes in muddy developments with garish real estate signs (SPANO, all yellow and red) or jingles (“Parkwood Homes you’ll agree are maintenance free, easy living for everyone”)

I generally assumed a developer came in, bought up a chunk of land from whomever owned it, and built away, on suburb at a time. Well, in the 1950s and 1960s, that may have well been the case with Parkwood Manor or Levittown, PA, but it was not the case with those suburbs that started up in the 1910s and 1920s, developed piecemeal, and were interrupted by the Depression and World War II. Penn Wynne was one of those places. The first clue should have been the homes. They were not uniform. Some were brick, some were stone, and some were frame and masonry or shingle. And it often varied from block to block. They were different because they were built at different times. But to a kid living in what was an essential finished area (a few fallout shelters notwithstanding) in the 1960s, this was a fait accompli, and not a cause for reflection. Other people had history. You had a garage or a basement.

I apologize in advance for the amateurish graphics, but, as you’ll see, they serve a purpose. If you look to the black box at the bottom, that was basically what became the hood. Look above the box and you’ll see a purple box called Penn Wynne School, which was built in 1930. Go North and East down what is labelled the Route 30 bypass (aka Haverford Road) and you will see above purple box called Convent of the Sacred Heart, which went up in the early 1920s. Welcome to my Montgomery County in the 1960s–those were about the boundaries. If you wonder why I ever say “How did I end up in South Texas?” now you know.

Like most kids, I assumed that where I was had been there for ever. Which, of course, it was, albeit in considerably different form. Penn Wynne, well, I’ve done some digging, but the more you dig, the more you realize you really did not know. Most people will not care at all if I assumed that the neighborhood we were in had once been part of the estate of a certain Elizabeth Arnau. I now think that was wrong by half a mile or so, and, that around 1900 or so, the land belonged to the estate of a certain Hannah Russell. That’s a bit of a problem, because while I had managed to figure out a great deal about Ms Arnau, Ms Russell is a bit of a mystery. She clearly had a few bucks, because she shows up on excise tax lists as early as 1865, but that’s about it for now. And if you had an estate, like, who did not know you were rich?

What I had not suspected, to repeat, was piecemeal development, and the importance of a number of financial institutions in Philadelphia in it. Two that show up prominently on this map are Provident Trust and Provident Title (they were two sides of the same coin) and became Provident National Bank (PNB) which got merged out of independent existence in 1983. PNB was once famous for its colored weather forecasting sign on the downtown Philly skyline (old style), but its successor bank, PNC, took it down because it was aging dangerously. Right. Like me. But Penn Wynne was clearly a big part of the Provident Trust project. Provident Trust was an old Quaker bank that dated to the 1860s, and featured a long list of heavy WASP hitters on its various boards with names like Wistar and Longstreth as decoration. Now, what this tells an old Phildelphia hand was that Penn Wynne was part of an elite creation, sort of a poor man’s Main Line Annex, the Main Line being where the real money was. It’s hard to suppress the thought that the old money figured that you had to put the hoi polloi somewhere, especially the ones who were starting to staff the department stores, public schools, law offices, and other service sectors of Philadelphia’s then enormous industrial sector. Where better? It made sense at the time, although, as Richardson Dilworth, a progressive Philadelphia politician in the 1950s and charter member of the Social Register would say, the white suburbs would become a fiscal noose around the city. Honesty, as Dick learned, would get you booed out of office (he was particularly big in South Philly, which he thought of as a dumping ground for parking lots, stadia and other NIMBY-shit that my Italian relatives took big exception to). Anyway, if you know how to read the names and such, all of this makes a great deal of sense. And, as I said before, Penn Wynne fit the profile (https://thisgameisovercom.wordpress.com/wp-admin/post.php?post=1534&action=edit), eventually attracting even some of the less desirables to the area.

You’ll also notice “Overbrook Manor.” Heh. When I was a kid, this was the ritzy part of Penn Wynne, otherwise known as Greenhill Farms, or something similar, where the uber-cafone Italian Americans and Irish Americans lived and lorded it over the mere peasants on the other side of Haverford Road. Little did I know those folks were literally to the manor born, Overbrook Manor on this map. It was never intended to be for just us folks, see

The vision for the neighborhood began in 1892 with financier Anthony Drexel of Drexel & Co. and a group of investors known as the Drexel Syndicate. The Syndicate purchased the 171-acre John M. George Estate, later adding the Wistar Morris Estate (present day Church Road and vicinity). Drexel engaged the noted developer partnership of Herman Wendell and Walter Bassett Smith, who also developed the Pelham District in Northwest Philadelphia and Wayne in Montgomery County.

Anchored around the first (and oldest) stop on the Pennsylvania Railroad’s famed “Main Line”, Overbrook Farms represented an ideal in suburban, healthy living for those desiring a retreat from the grit of Philadelphia in its industrial heyday, whose breadth and vigor earned the city the nickname “Workshop of the World”. Modern sewers and clean water supply, generous lots and sidewalks, proximity to the lush Morris Park, as well as its own dedicated Overbrook Steam Heat Co. and Overbrook Electric Co. (both now defunct) were among the amenities offered in the early days.

Many of the various architectural styles that were popular in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are represented in the district. Although there are over twenty styles represented in the neighborhood, the majority of houses are Colonial Revival or Tudor Revival. Other styles from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the district include Arts & Crafts, Dutch Colonial Revival, Gothic Revival, Queen Anne, Prairie, Romanesque, and Shingle.

The residents of Overbrook Farms initially were mostly middle to upper-class families, including artists, politicians, merchants, bankers, lawyers, industrialists, and academics, many leaders and innovators in industry and social welfare. Today, Overbrook Farms retains most of the qualities of life for which it was designed, but has become decidedly more diverse with regard to race, religion, age, race, and identity.

Oh, yeah, decidedly more diverse, although I’d hate to tell you what I thought of the kids from the right side of the tracks. It’s actually kind of intriguing you know. Snobbery was baked into that area, although the original snobs would not have been real thrilled at the contractors and ambulance-chasers from Philly who succeeded them. I know I wasn’t. Dedicated steam company. Right. (the stuff in blue is from some modern tout)

Also notice if you will, the John H McClatchy plan in the far Northeast corner. Another big time developer, but this guy did his best work in Upper Darby, which is technically, I guess, where I was born. (https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/PA-02-DE31) This guy, unbeknownst to me, had spread some of his joys on the other side of the Convent of the Sacred Heart, where you may recall I served mass and watched girls as an altar boy. That convent school was famous in those days, and the Mexican writer Elena Poniatowska actually went to school there–back when the Church was THE Church. I sort of wonder whether her family had anything to do with the Institute of Our Ladies of the Sacred Heart, which was also news to me. Turns out they got diversity now too, which was not the case when only blonde goddesses roamed the grounds, and the one Italian American girl I knew there was never quite in my league either. Sigh. My how the world has changed.

I know. You’re going to ask me if I think the world was a better place when Penn Wynne was mostly an investment for the trustafarian class of Philadelphia? All them Social Register types who thought they were slumming it when they stooped to admit refugee Italian-Americans from Penn Wynne into the Ivy Halls of Princeton and Penn? Or How ’bout Hermann Hessenbruch who had a 19 acre estate (“Waldeck” as in Weimar Germany) on what is now Remington Road. No, he was born here, silly, and he was a successful Philadelphia tycoon whose family gave generously to Lankenau Hospital (which used to be the grounds of the Philadelphia Country Club) and, yes, Princeton! To whom she donated a vacation home for use of the faculty! Damn! Who knew? Oh my, a rising tides lifts all boats, unless it’s the Titanic.

Check out the NYT link for details. It’s is to a 1962 obit, and I dearly hope you can access it. Makes me proud to have spent some time around Penn Wynne and its tonier environs. Waldeck included.

See. And you didn’t think that wealth ultimately had a trickle down effect in America. You know, land of the free and home of the brave? Where Anyone can grow up to be President!!! And does.

You just never thought Donald Trump would be the ANYONE who proved the rule. Nobody ever said Democracy was always going to be fun, did they? But then Andy Jackson came along…….

Fly Eagles Fly.

PS Thanks to James Maule, I have another graphic data point with which to work–around 1915. There was, of course, no Penn Wynne, and the land is marked as Continenal Trust and Title (Philadelphia). There is one farm shown as the “Heritage Farm” probably up around Remington and Haverford. No idea.